Glass Heroes: The humble Swappa Crate, NZ’s original refill scheme

Refill and reuse schemes are experiencing something of a renaissance, but the granddad of them all, ABC Swappa Crate, is still leading the way by a long stretch.

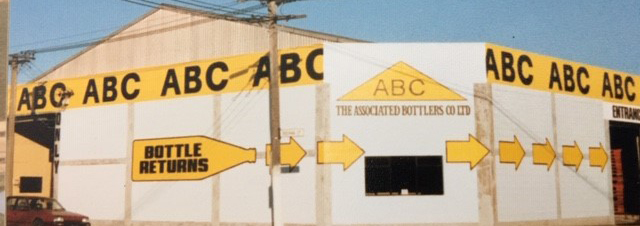

The scheme is owned by members of the Glass Packaging Forum, Lion and DB, and with the help of the Associated Bottler’s Co’s logistics operation, sees around six million bottles being reused, around four times each, per year. Studies have shown reusing bottles contributes to a low-emissions economy, with ABC Swappa Crate standing as a shining example of what is needed to run a nation-wide beverage refill scheme.

Philip Barlow has been at the helm of Swappa Crate for over 10 years. According to him, each of their bottles prevents the use of 39 single-use glass bottles of a similar size over its lifetime.

“Although there have been subtle changes in bottle design over 10 years ago, some of the old design ABC bottles are still going around and being refilled,” he says.

In recent years refillables schemes have gone from being seen as an old-fashioned way of doing things to being a hot topic in the conversation about the reduction of single-use packaging.

“Swappa Crate has definitely benefitted from increased public profile and support of refillables, undergoing a resurgence in popularity in recent years,” Philip says.

Rise and decline

At its peak, in 1975, some 336 million of ABC’s standardised bottles were used by New Zealanders to enjoy their favourite beer. This was a staggering 92% of the packaged beer market of the day –dominance which is almost unthinkable in today’s market of boutique craft breweries and imported specialty beers.

However, market trends began to change. Kegs became more prevalent in bars, reducing the need for bottled beer, while the cost of producing glass decreased to the point where single-use options became more attractive to brewers.

The cost of glass bottles has historically been at the heart of return and refill schemes. They were simply too expensive not to be recovered, so bottlers incentivised their return. However, the increasing demand from consumers for convenience meant single-use options became more popular.

Today the Swappa Crate scheme holds a far smaller portion of the market but as refill schemes grow in popularity so has Swappa Crate. From 2015 to the start of the pandemic saw the scheme grow 13% year-on-year. Lockdowns had a profound impact as Swappa Crates aren’t sold in supermarkets, but by 2021 the scheme had regained a substantial portion of the volume lost in 2020.

History

The scheme began with the establishment of the Auckland Bottling Company (ABC) in 1920, which set out to standardise the diverse range of beer bottles in the market. The move worked and soon ABC’s bottles became the standard for brewers in Auckland.

At the time New Zealand had no local glass bottle maker so the first standardised bottles were imported from Owens-Illinois (O-I) in the United States, with an initial order of 120,000 units In 1922 a glass manufacturing plant was set-up in Penrose (which was just outside Auckland at the time) meaning bottles could be sourced onshore, as they still are today.

The plant is now owned by Visy.

How it works

Swappa Crate, as its many loyal users will know, works on a simple and time-tested model of using standardised bottles to sell beer with its customers incentivised to return the bottles to be washed and refilled. The average bottle is reused around four times a year and lasts about 10 years, but some last as long as 15 years in the system, Philip says. Bottles which are deemed unsuitable for refilling are sent to be recycled.

Its ability to keep running for 103 years is thanks to the basic building blocks of any successful return and refill scheme: standardised bottles, established infrastructure to wash and refill bottles at multiples points around the country, reverse logistics built into an existing supply chain and easily accessible return points for the public.

Why it matters

Other than setting an example for how a large-scale refill scheme can be successful, the environmental impacts are obvious.

This is because reuse sits atop the waste hierarchy as it eliminates the need to manufacture new containers, thus saving the required energy and virgin (and recycled) materials. Additionally, many studies have found that reusing glass containers has a lower carbon impact than single use glass.

A report by Reloop & Zero Waste Europe (Reusable vs single use packaging: A review of environmental impacts) which looked at 32 life cycle analyses, found refillable glass bottles (on average) have 85% less emissions than single-use glass bottles.

A long-running and nation-wide reuse scheme also helps with normalising reuse and encouraging behaviour change around reuse and single-use.

Cheers to another 100 years?